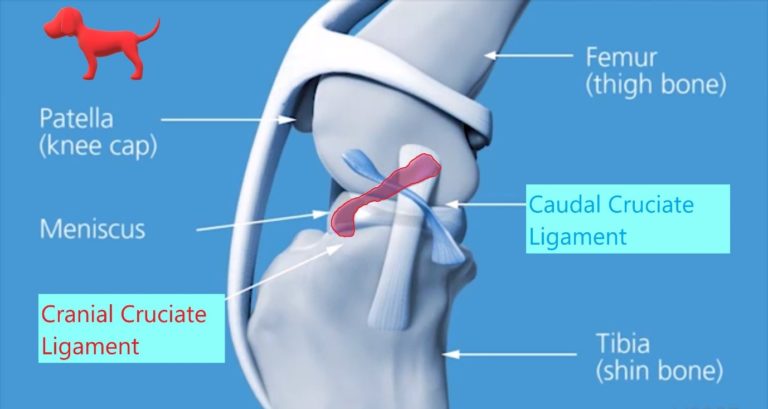

When the cranial cruciate ligament is torn or injured, the tibia (shin bone) slides forward with respect to the femur (thigh bone) every time the pet walks or tries to bear weight on the leg. This major instability is referred as a positive cranial drawer test.

Practically the two bones of the stifle (the tibia and femur) will rock back and forth during walking. This instability will lead to inflammation, pain and osteoarthritis (OA). Furthermore, due to this instability, many dogs with cranial cruciate ligament rupture will tear their menisci (‘shock absorbers’ cartilages of the knee). Torn cartilages can be very painful and can cause significant lameness and discomfort unless treated appropriately.

What is the cause of cruciate ligament injury in dogs?

Excessive trauma that leads to a sudden rupture of the cranial cruciate ligament is very rare in dogs.

In the vast majority of dogs, the cranial cruciate ligament ruptures as a result of progressive degeneration, whereby the fibres within the ligament become weaker and progressively tear just like a fraying rope. At that point minor stress like running in the park or chasing a ball may lead to a complete rupture.

The reason the cruciate ligament degenerates prior to rupturing is still not fully understood, with various genetic, environmental, and mechanical factors influencing disease progression. Certain breeds, such as Labradors and Rottweilers, are much more commonly affected than others.

As rupture of the cranial cruciate ligament is due to progressive degeneration of the ligament, both stifles (knees) can be affected. The incidence of bilateral cranial cruciate ligament rupture in dogs has been reported to range from 18 to 61%. When bilateral rupture happens, most frequently one leg will be affected first and the second at some point in the future.

What are the signs of cranial cruciate ligament rupture?

The signs associated with cranial cruciate ligament disease can go from a subtle lameness to complete non-weight-bearing lameness.

The initial stages of the condition can be subtle (stiffness after rest and mild, occasional lameness) and may be initially missed. As the ligament continues to tear the lameness may become more obvious. You may notice that your dog starts sitting with hind legs out to the side. Occasionally a clicking/popping noise (which may indicate a meniscal tear) can be heard.

When both legs are affected difficulty rising from a sit and jumping are commonly noticed.

How is cranial cruciate ligament disease diagnosed?

Diagnosis is usually based on orthopaedic examination by a veterinary surgeon.

During the examination your pet will be assessed for the typical clinical signs of cranial cruciate ligament disease. Those include pain at joint manipulation, joint swelling, and joint instability (see video).

In some cases, palpation under sedation or light anaesthesia may be necessary to enable the detection of more subtle instability of the knee (partial or chronic rupture of the cranial cruciate ligament).

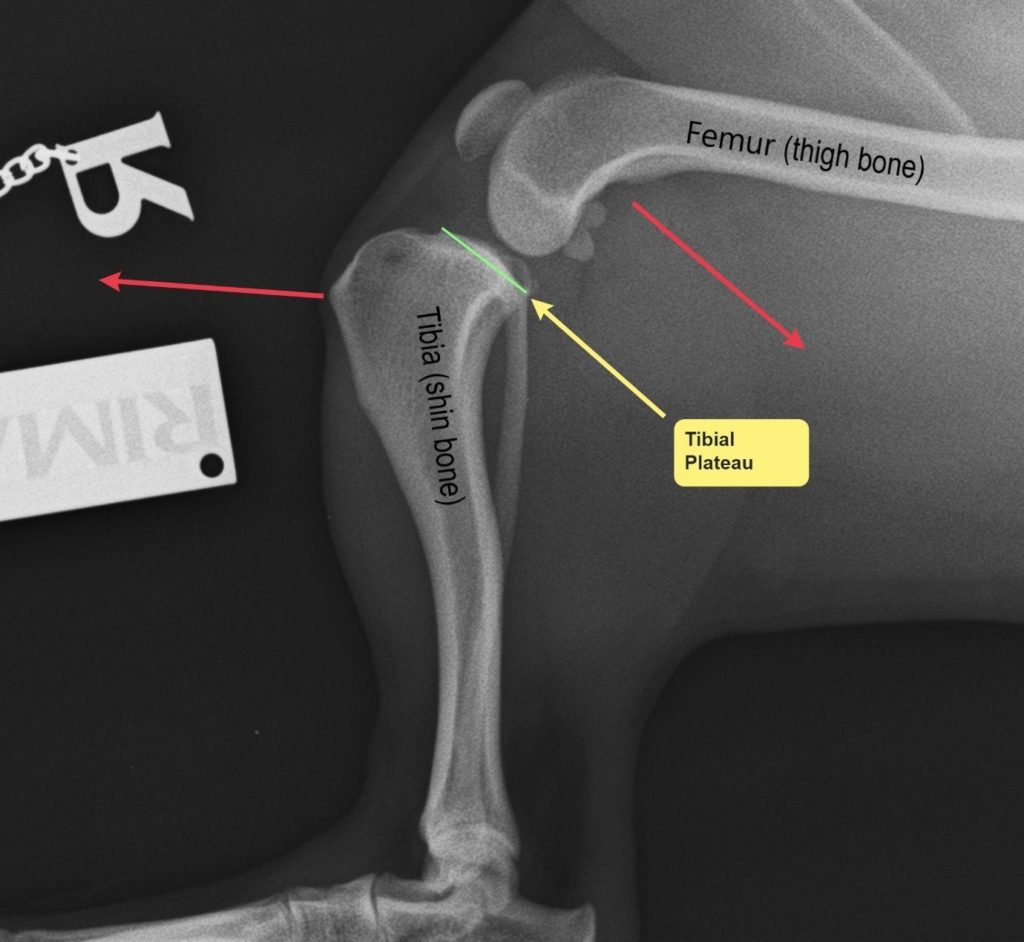

Radiographs of the affected stifle should be performed to confirm the diagnosis and evaluate the joint.

As the likelihood of cranial cruciate rupture in the contralateral leg increases if radiographic signs of osteoarthritis are already visible in the contralateral joint, we recommend taking radiographs of both stifles.

The radiographs may also be needed to plan the surgery.

Positive cranial drawer test.

Diagnosis of CCL rupture require an assessment of stifle joint stability by means of the cranial “drawer” test. The ability to move the tibia (shinbone) forward with respect to a fixed femur (thigh bone) is a positive cranial drawer sign indicative of a CCL rupture.

How can cranial cruciate ligament rupture be treated?

Non-surgical management

Includes long periods of restricted activity, weight management, medical treatment (pain killers) and physiotherapy. Small and slim dogs (usually less than 10 kg) may do ok with a non-surgical management, although surgery is generally considered to offer a quicker and more reliable recovery. In some small dogs (particularly terriers) the conformation of their shinbone can mean that they are less likely to get better without surgery. In medium and large breed dog non-surgical management is seldom recommended, except where the risks of a general anaesthetic or surgery are considered too high due to other severe diseases.

Surgical management

Several surgical techniques have been described to treat cranial cruciate ligament problems and they are generally divided into two main groups:

Techniques that aim to replace the damaged ligament

Known as extracapsular or lateral retinacular suture or fabello-tibial tuberosity suture: a restraining suture is placed around the stifle joint to try to replicate the function of the torn ligament. This can be a good technique for small dogs but there is a significant risk of suture stretching/failure which can result in recurrent instability. We generally do not advise this technique in dog weighting more than 10 Kg. The main advantages of this technique include the lower cost and the lack of a bone cut (meaning that potential complications associated with the bone cut are not seen with this technique). A number of terrier breeds and particularly the West Highland White Terriers, have an extremely marked backward slope to the tibial plateau. This is believed to be associated with a reduced response to lateral suture repair. For this reason, we often recommend a TPLO procedure in these animals despite their small size.

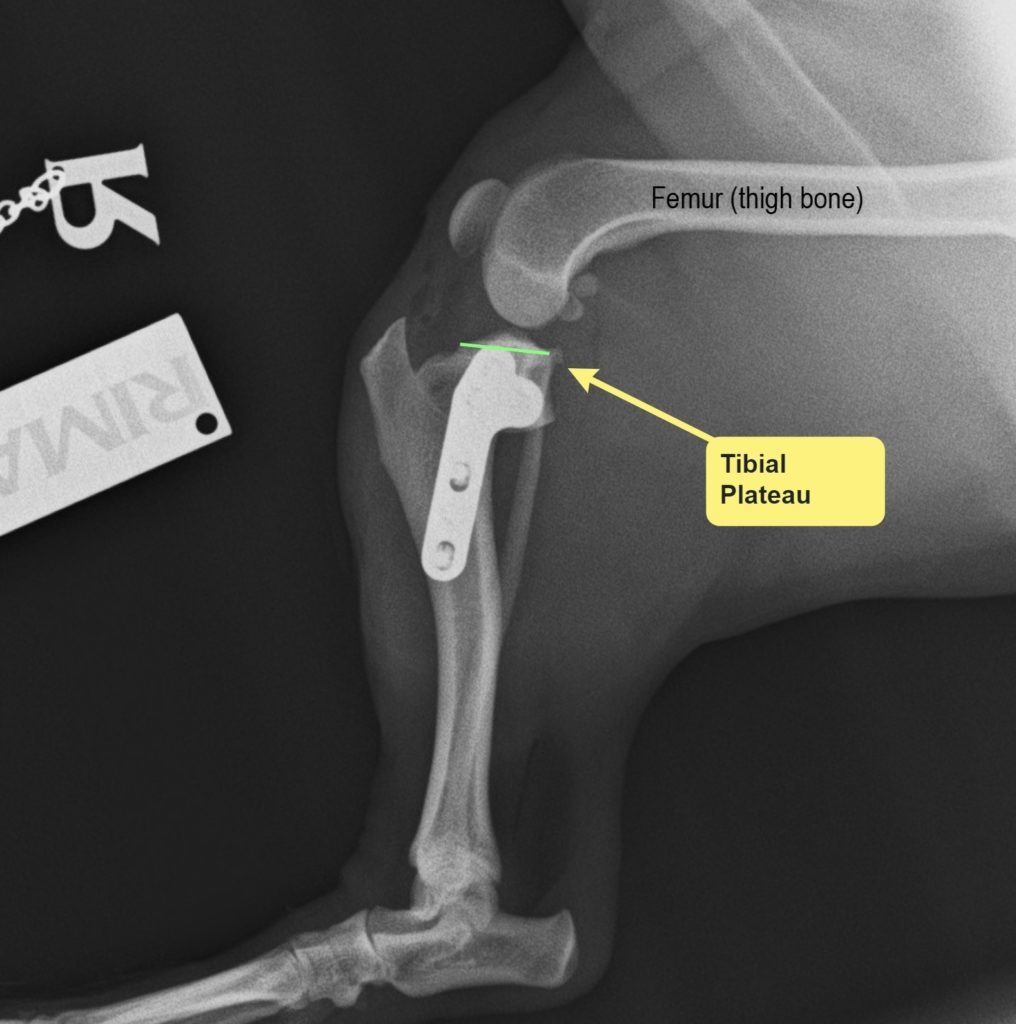

Tibial osteotomy techniques such as Tibial Plateau Levelling osteotomy (TPLO) and Tibial Tuberosity Advancement (TTA, also referred to as MMP)

These techniques aim to render the ligament redundant (unnecessary) by cutting the tibia (shinbone) and changing the forces acting on the knee (stifle joint) during weight bearing. In most cases, these techniques result in faster recoveries and, of these, TPLO appears to be the most robust technique. Published research studies confirm that TPLO returns dogs to better limb function than suture stabilisation in the short and medium term and that TPLO is superior to TTA. TPLO is associated with lower complication rates, an improved clinical-functional outcome and less increase of arthritis compared to TTA.

Surgery for meniscal injuries

Many dogs with cranial cruciate ligament rupture will injure their menisci (‘shock absorbers’ cartilages of the knee). Torn cartilages can be very painful and can cause significant lameness and discomfort unless treated appropriately. Regardless of the type of surgery chosen to stabilize the stifle, all dog will have inspection of the joint to assess whether secondary injuries to the menisci have occurred. If an injury is found, this is treated surgically by removing the damaged portion. There is however an approximately 10% risk of an injury to the meniscus at a later date. This generally appears as a patient that has recovered well from surgery and then starts to limp on the leg again. Should this occur then a small surgery with quicker recovery time for removal of the damaged part of meniscus will be necessary.

TPLO: What is it, and why choose that?

TPLO is an abbreviation for Tibial Plateau Leveling Osteotomy and is a surgical procedure which aims to change the forces acting on the knee (stifle joint) to reduce the instability and pain caused by cranial cruciate ligament rupture.

In dogs the articular surface of the top of the tibia (Tibial Plateau) has a posterior inclination (tibial slope) that is much higher than in peoples. With a tibial plateau angle (TPA) that can range from 20° to 30° or even more.

Because of this inclined articular surface, the forces acting on the stifle during walking are cranially directed. An intact cranial cruciate ligament will offset these forces and keep the stifle stable; However, when the ligament is torn, the tibia (shin bone) will slide forward with respect to the femur (thigh bone) every time the pet walks or weight bears. This major instability is referred as a positive drawer sign.

Postoperative care

Correct postoperative management after TPLO is crucial for a successful outcome. A postoperative plan will be discussed with the owner during the consultation.

All pets that have a TPLO surgery performed with us are sent home with a detailed written post-operative instruction plan.

The plan will most likely include restricted kennel rest and controlled muscle-building activities (ie, leash walking) for 8 weeks or until the bone is completely healed.

At 8 weeks postoperatively radiographs of the stifle will be performed to assess healing of the osteotomy.

Postoperative rehabilitation will be discussed to develop a program to help return your pet to full functioning. Physiotherapy activities including hydrotherapy will be discussed.